When I was a kid, I watched my dad park the car and retrieve a notebook from the glove box. There, he carefully recorded the details of our trip: Kilometers done, fuel usage, the price of petrol. I asked him why. He said it was so he could track the fuel economy and the wear on the tires and make sure he wasn’t running some gas-guzzler of a vehicle that was more expense than sense.

Two decades later, as I plugged numbers into a spreadsheet, it occurred to me that most people probably don’t track the distance they walk each week… or the shoes they’re wearing at the time. I might not track my fuel economy, but I track where the rubber meets the road. Essentially, I was doing the same thing as my dad.

I don’t own a car. To get around, I walk, bike, or take public transport. Most often — say, 90% of the time — I walk. Which means wearing shoes. Which means wearing out my shoes at a great rate of knots.

Do I have an entire separate category in PocketSmith just for my footwear? I sure do. It gets an annual budget, and I adjust it as needed. For example, the balance as of May 2024: $450 spent out of $900 budgeted. Milage up until that point: 1,135km.

“You rack up the miles more than almost anyone else I know.” — Direct quote from the owner of our local Frontrunner shop, a guy who runs ultramarathons at the weekend. For fun.

Well, for his definition of fun, at least.

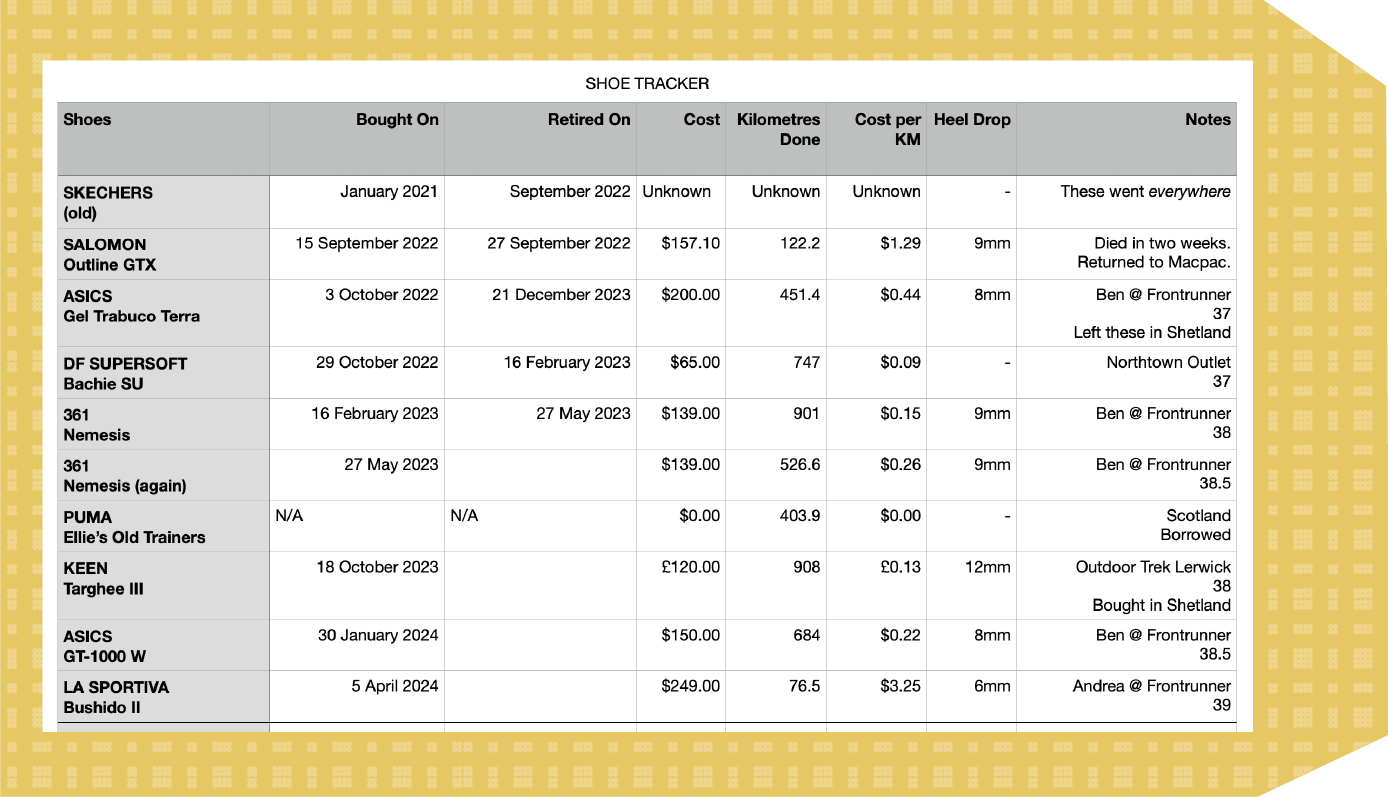

The tracker spreadsheet is simple. It started as part of Wilderness Magazine’s Walk1200KM challenge. I check my iPhone’s fitness tracker, plug in my daily kilometers walked, and then keep a running tally for whatever shoes I was wearing at the time. I’ve been tracking it for a few years now. That’s long enough to know what my average spend on a pair of shoes is, how long they should last me, and to warn me when I need to replace them.

The recommendation from the Strava sports app and from most footwear companies is that you should look at replacing shoes every 500-ish kilometres to avoid increased risk of injury. Considering I mostly do low-impact exercise like walking and that I can cover 500km in 6-8 weeks, that would be a lot of new shoes for no real reason.

Instead, I track my distance and keep a note of when they start to feel uncomfortable. On average, a pair of shoes lasts me 600-700km before I start noticing any discomfort. I can generally go to 750-800km before risking blisters. Beyond 850-900km, they’re only good for mucking in the garden at the weekend.

That’s almost twice the official recommendation — which means my money goes twice as far.

The most expensive pair of shoes I’ve bought in the last three years were chunky, waterproof Keens. They’re the most comfortable shoes I’ve ever had, and they weren’t on sale: They cost me £120 ($240) in Shetland. They’ve lasted just over 900km at the last check.

The cheapest pair were basic black trainers from some brand I’d never even heard of called Superset. They were on clearance at an outlet shop. They cost me $65 in New Zealand, and they lasted 750km.

It’s tempting to make blanket statements like “cheap shoes aren’t worth it.” Usually, I’d agree. Cheap shoes wear out faster, they’re worse for your feet, and they’re made under incredibly unethical conditions in sweatshops. The last time I bought shoes from The Warehouse, years ago now, I could feel them wearing out by the end of the first week.

But sometimes, a great deal is worth it.

The cost per kilometre on the Keens? 13p, or about 26 cents. That’s still good value, don’t get me wrong!

The cost per kilometre on the El Cheapo Supersofts? An incredible 9 cents.

“The reason that the rich were so rich, Vimes reasoned, was because they managed to spend less money.

Take boots, for example. He earned thirty-eight dollars a month plus allowances. A really good pair of leather boots cost fifty dollars. But an affordable pair of boots, which were sort of okay for a season or two and then leaked like hell when the cardboard gave out, cost about ten dollars. Those were the kind of boots Vimes always bought, and wore until the soles were so thin that he could tell where he was in Ankh-Morpork on a foggy night by the feel of the cobbles.

But the thing was that good boots lasted for years and years. A man who could afford fifty dollars had a pair of boots that’d still be keeping his feet dry in ten years’ time, while the poor man who could only afford cheap boots would have spent a hundred dollars on boots in the same time and would still have wet feet.

This was the Captain Samuel Vimes ‘Boots’ theory of socioeconomic unfairness.”

― Men at Arms by Terry Pratchett.

Rachel E. Wilson is an author and freelance writer based in New Zealand. She has been, variously, administrator at an ESOL non-profit, transcriber for a historian, and technical document controller at a french fry factory. She has a keen interest in financial literacy and design, and a growing collection of houseplants (pun intended).